At the intersection of the Venn diagram of ways to achieve greatness, Shohei Ohtani makes for a population of one.

There have been 701 games in which a player hit three home runs, postseason included. There have been 10,259 games in which a pitcher struck out 10 batters or more. Those sets of greatness had never intersected, nor would anybody expect them to, until Ohtani rewired our minds to what is possible.

It is a rare day in sports when an athlete plants a flag on unchartered ground. We are accustomed to records being broken—home runs in a season, rushing yards in a game, points in a career, etc. It’s a game of perpetual leapfrog. But the invention of achievement in a game that’s been around for a century and a half should stir wonder in even the most jaded of souls.

On top of the singularity of the performance, the timing of Ohtani’s mastery of two distinct skills heightened its historical importance. The Dodgers won the pennant behind the pitching and hitting of Ohtani in Game 4 of the National League Championship Series against Milwaukee.

Even if you considered only what Ohtani did on the mound you would be placing it among historically great games. It was only the second time in postseason history a pitcher won a clinching game by pitching shutout baseball with 10 strikeouts and no more than two hits allowed. The other was by Justin Verlander, but not with the World Series on the line (2013 ALDS).

Until that night it would seem impossible that a pitcher of such caliber would also club three home runs, let alone massive blasts that traveled 427 feet, 446 feet and, going clear out of Dodger Stadium, 469 feet. In one night, Ohtani hit more home runs of 440 feet or more than he has allowed on the mound in 102 career games (1). He hit the three hardest balls of the night (113.6 mph or more) and threw the 11 fastest pitches of the night (99.2 mph or more). That’s madness.

Go ahead, knock yourself out trying to find an athlete who had a day of greater achievement, especially when it comes to the breadth of skills. Maybe you must stretch the locale of achievement beyond the boundaries of the field. In the 2007 Fiesta Bowl, for instance, Boise State running back Ian Johnson scored the winning two-point conversion to upset Oklahoma, then dropped to a knee to ask his girlfriend, a cheerleader, to marry him. (She said yes.)

Umpire John Tumpane in 2017 saved a woman who was about to jump off the Roberto Clemente Bridge, then a few hours later proceeded to call balls and strikes with the Clemente Bridge looming in his sightline.

Those are great days in sports. To find anything even close to what Ohtani did on the field of competition, Sports Illustrated scoured the major sports for the best individual performances.

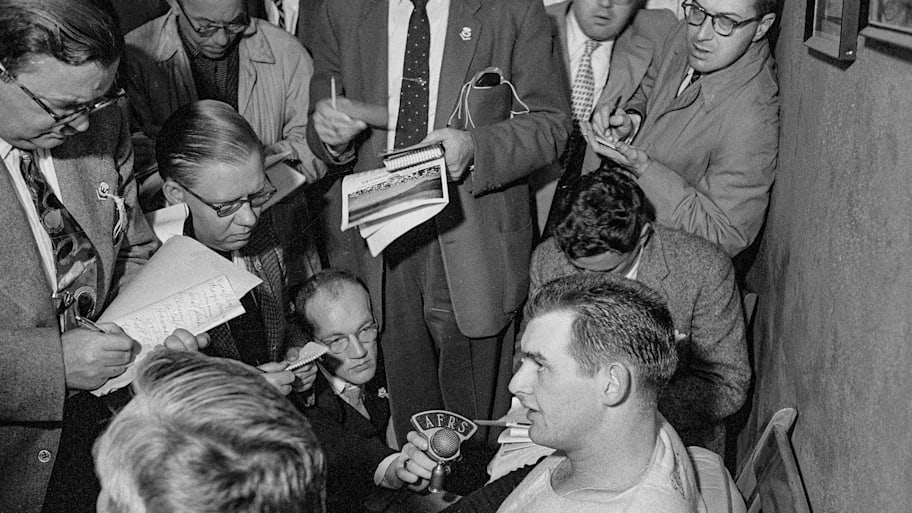

MLB: Don Larsen

How could you be better than perfect? Don Larsen of the Yankees retired all 27 batters he faced in Game 5 of the 1956 World Series to win, 2–0. It was never done in the World Series before, and it has never been done in the postseason since.

On the biggest stage and with the World Series tied two games each, Larsen threw 97 pitches and had one three-ball count. Known as an eccentric (he smashed his car at 5 a.m. in spring training), Larsen ditched his windup a few weeks earlier as a defense against a Red Sox coach who was expert at picking up pitch-tipping tells. His no-windup delivery flummoxed the Dodgers, who had five future Hall of Famers in their lineup (Pee Wee Reese, Duke Snider, Jackie Robinson, Gil Hodges and Roy Campanella).

So dominant was Larsen that after the game Robinson walked over to the Yankees’ clubhouse to shake his hand and personally congratulate him. “I’m still a youngster in this game,” Robinson told Larsen, “but this was by far the finest pitching performance I’ve ever seen.”

Greater than Ohtani? Because of his three homers and his pitching, Ohtani was better than perfect. Larsen was 0-for-2 at the plate that day. —Tom Verducci

NFL: Tom Brady and Gayle Sayers

The easy answer here is the correct one: Tom Brady becoming the first quarterback ever to win five Super Bowls after leading the Patriots back from a seemingly-insurmountable 28–3 deficit against the Falcons in February 2017. The Falcons led with 8:31 left in the third quarter, and Brady had to be just about perfect from that point forward for New England to even have a chance. —Albert Breer

Or is it Gayle Sayers, who was transcending something when he essentially levitated over a sloppy and disgusting Wrigley Field to score six touchdowns against the 7–6 49ers back in 1965. Sayers scored on an 80-yard pass, 21-yard rush, 7-yard rush, 1-yard rush and 85-yard punt return. —Conor Orr

Greater than Ohtani? Orr and Breer make their cases here for these two very different NFL feats.

Men’s basketball: Magic Johnson and Christian Laettner

Atop Magic Johnson’s lengthy list of accomplishments is one that makes a compelling case for the greatest accomplishment in NBA history: 42 points, 15 rebounds and seven assists in Game 6 of the 1980 NBA Finals. After losing Kareem Abdul-Jabbar late in Game 5, the Lakers flew to Philly, where Los Angeles’s flashy, 6’ 9” rookie point guard took over. —Chris Mannix

All it took to win the 1992 NCAA Tournament East Region championship and earn a Final Four berth was perfection. Christian Laettner supplied it. In Duke’s classic, 104–103 overtime victory over Kentucky, Laettner made all 10 of his field goal attempts and all 10 of his free throws and finished with 31 points. —Pat Forde

Greater than Ohtani? Mannix considers the hefty two-way play of both Ohtani and Johnson in close-out games in a playoff series, while Forde looks at Laettner’s legendary perfection here.

Tennis: Novak Djokovic and Serena Williams

Before the 2024 season, Novak Djokovic had called his shot, Babe Ruth style, announcing to the world his ambition to win Olympic gold for Serbia, the lone missing entry on his unrivaled tennis résumé. In what he deemed the biggest match of his life, he played near flawless tennis. His shots licked the lines; he outserved his younger opponent, Carlos Alcaraz; above all, he won the points freighted with the most pressure. Djokovic prevailed 7–6, 7–6.

Serena Williams’s first major title was the ultimate act of foreshadowing. Age 17 and regarded as not even the best player in her own family, she went from “respected” to “feared” in a matter of days, beating four future Hall of Famers to reach the 1999 U.S. Open final. There, Serena faced Martina Hingis, the top seed and world’s No.1 player. —Jon Wertheim

Greater than Ohtani? Wertheim argues here that one of these just might have been…

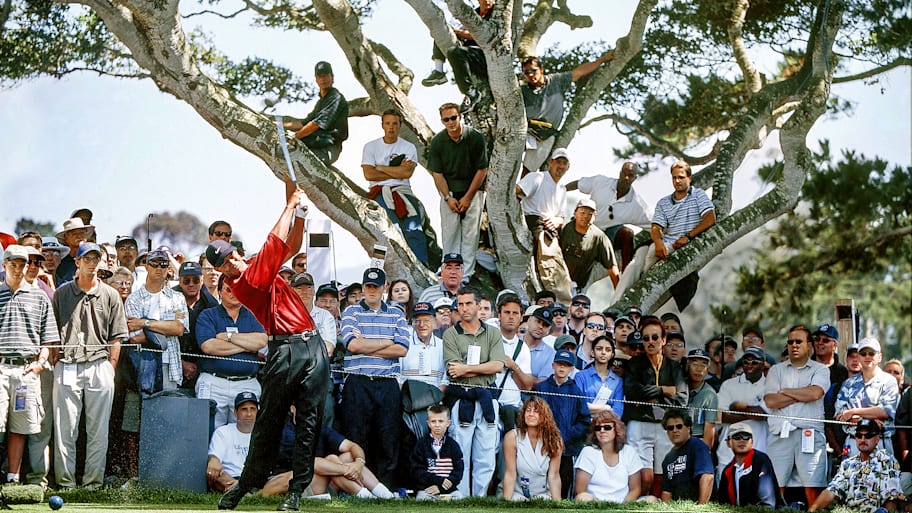

Golf: Tiger Woods and Karrie Webb

Tiger Woods set a major championship record when he was the only player under par, shooting 12 under at Pebble Beach to win the 2000 U.S. Open by 15 strokes. Woods had two bogey-free rounds while the other 155 players in the field combined for one. And he made just six bogeys or worse over 72 holes. —Bob Harig

Annika Sorenstam and Karrie Webb were the headline rivals of the LPGA as the calendar turned to 2000, but Webb put a temporary end to the argument with a 10-shot win at the Nabisco Championship—her fifth win in six starts. Webb went wire-to-wire at Mission Hills Country Club, and put a cap on it all, making a Sunday hole-in-one on the way to finish 14 under. —John Schwarb

Greater than Ohtani? Harig and Schwarb explain here that both baseball and golf knew who their very best were in these moments of sports history.

Swimming: Leon Marchand and Katie Ledecky

While Michael Phelps winning gold medals on the same day in the 200-meter butterfly and 800-meter freestyle relay at the 2008 Beijing Olympics should be considered, Leon Marchand had a double that didn’t involve a relay. The Frenchman’s 200-meter breaststroke/200-meter butterfly double gold blew the roof off the venue at the 2024 Paris Olympics, achieving both in a span of two hours and setting Olympic records in both events.

Katie Ledecky, queen of all freestyle, showed some Ohtani-esque versatility in 2015 better than any woman has. On Aug. 4 at World Aquatics Championships, Ledecky dove in for a preliminary heat of the 200-meter free, qualifying first for the semifinals that night. But before she could swim that semi, she had to take care of the 1,500-meter free, during which she set a world record that would stand for three years, until she broke it again. —P.F.

Greater than Ohtani? Forde states his case here that one of these seemingly tireless swimmers could reach Ohtani’s threshold of greatness.

Gymnastics: Kenzo Shirai and Maria Gorokhovskaya

On Oct. 5, 2013, at the World Championships in Antwerp, Belgium, 17-year-old Japanese gymnast Kenzo Shirai debuted two brand-new skills in the final of the floor exercise, a backward quadruple-twisting layout somersault (named the Shirai for him), and a forward triple-twisting layout somersault (named the Shirai II). His routine contained a preposterous 22 ¼ twists and made him the youngest male world champion in the event.

The greatest day in women’s gymnastics history has to be July 23, 1952, when Soviet gymnast Maria Gorokhovskaya won five medals—one gold, in the individual all-around, and four silvers, one each in the floor exercise, the vault, the uneven bars and the balance beam. That was the most Olympic medals ever for a woman—and she won them in a day. —Stephanie Apstein

Greater than Ohtani? Apstein explains here why one of these gymnasts just might be better than Ohtani, but is open to further consideration.

Soccer: Zinedine Zidane and Marta

France’s World Cup quarterfinal against defending champion Brazil in 2006 was a one-man masterclass. Zinedine Zidane, who delivered several dazzling sequences and set up the only goal of the game, was gliding around knowing this was his last tournament before retirement. This was Zidane unshackled. —Grey Whitebloom

The U.S. women’s national team was on a 51-match unbeaten streak when it walked out to face Brazil in the semifinal of the 2007 Women’s World Cup, where 47,818 people at Yellow Dragon Stadium, in Hangzhou, China, gazed out assuming the favored Americans would advance. Instead, the fans were treated to Marta, who had two goals, an assist as the greatest powerhouse in women’s soccer tasted its biggest tournament defeat. —Theo Lloyd-Hughes

Greater than Ohtani? Whitebloom and Lloyd-Hughes ponder these international football greats here against the Japanese wizard of baseball.

Women’s basketball: Maya Moore and Sheryl Swoopes

There are (just a few) other players who have dropped 40 points in the WNBA playoffs. But there are none who have done it to lead their team to victory in such a close game, while also making an impact on so many other areas of the floor like Maya Moore in the 2015 semifinals. The Lynx’ 72–71 win over the Mercury hinged entirely on Moore, who also had eight rebounds, four assists and three steals to send Minnesota to the Finals.

While there are some compelling possibilities for college hoops, it’s best not to overcomplicate this. There’s a reason that Sheryl Swoopes’s 47 points in the 1993 national championship traditionally gets this nod. No one has ever come up bigger in a title game. Swoopes was a virtually unstoppable scoring threat in the lane, behind the arc and at the line, and brought Texas Tech its first and only title with an 84–82 win over Ohio State. —Emma Baccellieri

Greater than Ohtani? Baccellieri analyzes here the impact Moore and Swoopes had in their clutch postseason performances compared to Ohtani.

College football: Vince Young

The greatest college football game of the 21st century was decided by the greatest individual effort of any century, when Texas quarterback Vince Young simply said: I’m taking over. Young led Texas to the 2005 national championship with a thrilling victory over USC, 41–38 He threw for 267 yards that night and ran for another 200 and three touchdowns. USC had its 34-game winning streak snapped, denying the Trojans a national title three-peat. —P.F.

Greater than Otani? Forde considers here if the dual-threat quarterback is as versatile as the Dodgers’ two-way threat.

NHL: Dominik Hasek’s 70-save shutout

On April 27, 1994, the Devils walked into Buffalo Memorial Auditorium and a wall. The best goalie in NHL history put on the best performance of his life.

Facing elimination, against a team that finished second in the NHL in goals and would win the Stanley Cup the following season, the Sabres’ Dominik Hasek pitched two shutouts in one night. He had 70 saves in a four-overtime 1–0 win, forcing a Game 7.

Shots on goal can be a misleading stat. But if you watch all 70 of Hasek’s saves, you’ll see: The Devils had a ton of great chances. Hasek stopped two-on-ones and breakaways and rebounds and shots when he appeared to be screened. He did it all in his inimitable style, an unconventional fusion of unparalleled reflexes, athleticism and intuition. Hasek wasn’t just better than other goalies, he was an unsolvable mystery.

On his 63rd save, he dropped his stick. He made his 67th save lying on his back, with his head facing away from the man who shot it, Bill Guerin. The game ended at 1:52 am—six hours and 13 minutes after it began. Hasek went on to stop 44 of 46 shots in a Game 7 loss. But Game 6 was his masterpiece.

Greater than Ohtani? No. Hasek did what other great goalies have done, except better. —Michael Rosenberg

MMA: Holly Holm takes Ronda Rousey’s title in 2015

This was the UFC’s equivalent of Tyson-Douglas in Tokyo. A champion (Ronda Rousey) who wasn’t merely winning fights but dominating, instilling fear and winning six straight title defenses, often in a matter of seconds. A seasoned challenger (Holly Holm) who entered with little oddsmakers chance, and little profile, but also little fear. A far-flung location (Melbourne) that added to the surreal vibes. First, Holm survived Rousey’s onslaught. Then, she began to initiate the action. As she connected with fists and kicks and elbows, landing the majority of the significant strikes, Holm’s confidence swelled as Rousey’s face swelled. Then, late in the second round, it came: a high left kick that collided violently with Rousey’s head and ended the fight … a perfectly executed strike to cap off a perfectly executed fightplan. Rousey would never be the same fighter and before long would decamp to the WWE. As the new bantamweight champ, Holm would never replicate this high. But for one night, it was mixed, it was martial, it was art … MMA at its most elevated.

Greater than Ohtani? Can we call it a technical draw? —J.W.

This article was originally published on www.si.com as Greater Than Ohtani? How Other Top Performances Match Up Against the Dodgers’ Two-Way Star.